Jealousy is a common and powerful emotion, one that draws in a number of other powerful ‘negative’ emotions such as anger, anxiety, fear and hurt. It is one of the top causes of homicide by spouses internationally and is experienced more by men (60% v 40%) than women. Even when this is not the case it can cause serious disturbance to relationships and to the people involved, creating severe limitations to the freedom of both the sufferer and their partner.

Jealousy is a common and powerful emotion, one that draws in a number of other powerful ‘negative’ emotions such as anger, anxiety, fear and hurt. It is one of the top causes of homicide by spouses internationally and is experienced more by men (60% v 40%) than women. Even when this is not the case it can cause serious disturbance to relationships and to the people involved, creating severe limitations to the freedom of both the sufferer and their partner.

This post explores jealousy from a number of angles considering:

- What jealousy is (and isn’t)

- Why we experience it

- How we experience jealousy

- How it functions

- How we can manage it—(skip to here if you’re only interested in this part)

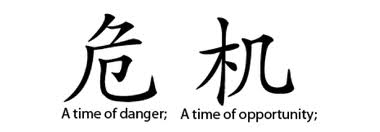

It will become clear that like many ‘negative’ (discomforting may be a better word) emotions jealousy is not all bad—there is such a thing as healthy jealousy, indeed, the absence of any jealousy may reduce the quality of a relationship.

What is Jealousy ?

Jealousy is often confused with envy but the two are quite different: envy tends to be focussed around a desire to have what someone else has (be it qualities, looks, possessions, status etc.) or a wish that they didn’t have those things and usually involves one other person; jealousy involves you, someone you’re attached to (maybe romantically) and a third-party perceived as a rival for your loved-one’s affections and exclusive relationship with you. Jealousy is generally a ‘triangular’ three-person dynamic, whereas envy is a two-person dynamic. Needless to say envy and jealousy may overlap.

There are different levels and types of jealousy ranging from clinical ‘delusional’ jealousy (involving obsessive and severe levels of disturbance that are persistent and unrelenting affecting only about 1% of the population) to ‘normal’ jealousy affecting most of us in varying degrees. Within ‘normal’ jealousy we can further subdivide it into categories of ‘healthy’ and ‘unhealthy’ jealousy. According to some researchers men tend to focus their jealousies around anxiety over sexual infidelity whereas women are more likely to be jealous over possible emotional infidelity. This is disputed however by some researchers who suggest that when different methodology is used both men and women experience similar concerns over sexual infidelity and, furthermore, when you allow for other factors that make men more likely to be aggressive it turns out men and women are just as likely to kill because of jealousy. Cultural discrepancies would suggest it’s not all down to genes.

http://www.nytimes.com/2002/10/08/health/jealous-maybe-it-s-genetic-maybe-not.html

Why We Experience Jealousy

Jealousy does not come out of nowhere. Evolutionary psychologists would suggest that a large factor is the need of males to ensure that any progeny they father is actually theirs—it’s of no advantage to be raising a rival’s offspring and committing serious resources to the endeavour. Males, on this understanding have an interest in feeling alarmed so that they can fight off rival mates for the female. Of course, individuals will be unaware of the evolutionary causes that have shaped the mind but it certainly makes sense that jealousy-capable animals will fare better in securing their genetic investments. Females, equally, do not want to find they have taken on a male that will not stick around and support her and her offspring by attaching to a rival female. Culture is a factor too and we see differing sexual versus emotional jealousy in different cultures—Chinese men, for example, posit emotional-infidelity scenarios as more jealousy-provoking than sexual infidelity scenarios.

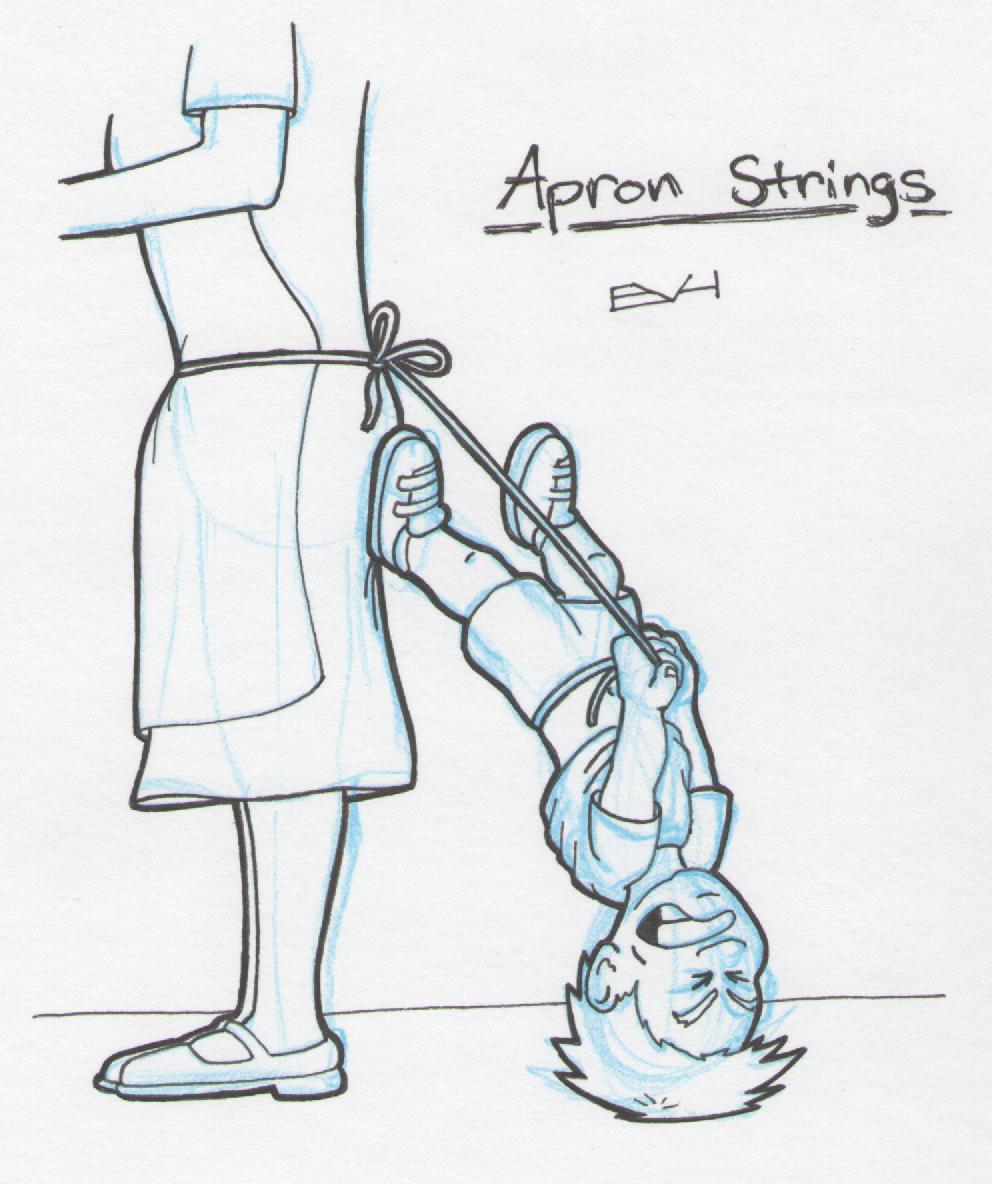

The main personal reasons we experience jealousy is because of past experiences: we have been burned in previous relationships or we have experienced displacing rivalry in childhood—or both. The Oedipal dynamics whereby we experienced the loss of maternal or paternal attention—or perceived this–due to the other parent or a sibling taking some of it away. We needn’t buy into a full acceptance of a Freudian view that at an early stage boys desire to sleep with their mothers and feel threatened that their fathers wish to castrate them to see that children—girls no less than boys—experience losses when a third party vies for attention. How we respond as adults to the potential vying of attention when a third party arrives on the scene is often deeply influenced by these formative years although some of it will have been learnt in the stages prior to our ability to remember or verbalise.

The main personal reasons we experience jealousy is because of past experiences: we have been burned in previous relationships or we have experienced displacing rivalry in childhood—or both. The Oedipal dynamics whereby we experienced the loss of maternal or paternal attention—or perceived this–due to the other parent or a sibling taking some of it away. We needn’t buy into a full acceptance of a Freudian view that at an early stage boys desire to sleep with their mothers and feel threatened that their fathers wish to castrate them to see that children—girls no less than boys—experience losses when a third party vies for attention. How we respond as adults to the potential vying of attention when a third party arrives on the scene is often deeply influenced by these formative years although some of it will have been learnt in the stages prior to our ability to remember or verbalise.

Attachment theory provides evidence that if we didn’t develop a sense of worth and security in childhood with our mother (or father, whoever was our primary caretaker) we are more likely to have found difficulty in adapting to the intrusion of a ‘third’. Insecure attachment can result in a clingy need to merge or anxiously vouchsafe the presence of a close loved one adding to the fear of their potential loss. Equally, we may have learnt to respond with an ‘avoidant’ attachment style which is still marked by anxiety but managed by withdrawal and distancing strategies to diminish pain—either way, underneath it all, there lurks an anxiety that exacerbates fear of loss.

How We Experience Jealousy

Jealousy is a powerful and discomforting emotional mind-set. It is important to realize that it is very common and not necessarily negative. It can have positive effects: it can galvanize action to save a relationship, it can stir us from apathy and low-effort, it can arouse us to appreciate the value of a relationship. This is the healthy side, the side of it that is an effective and constructive response to reality; it becomes unhealthy when it isn’t based in reality and/or isn’t constructive.

Unhealthy jealousy often manifests as a desire to control against potential loss. This entails trying to control the parts of the triangle (you, your partner, a potential rival) involved. At the same time it can be marked by self-undermining shame: the emotional belief that you are just not good-enough and that your partner is bound to desire the first reasonably attractive person (usually of the opposite sex) that comes along and so there is the possibility of constant need to put on an attractive front. The pressure can be immense in such a scenario: pressure is applied to oneself to be better than an imagined rival; pressure is put on a partner to think, feel and behave (or not behave) in certain ways and pressure is sometimes placed on external relationships—to keep their distance.

Because unhealthy jealousy is usually not based on real world (evidenced) facts it is something being played out in the individual’s inner world. For this reason it is not usually specific to limited scenarios but is a lens that colours everything they see. It can affect them even when no rival is around and even when they’re alone. If jealousy is controlling you it will influence how you feel watching scenes on TV, what conversation topics you avoid, what plans you make—anything that causes you to worry about what your partner may begin to think, feel or desire.

As we’ve seen, this can play out with aggression and violence as the jealous person seeks to control either the partner or the perceived rival but for a great many this isn’t the case. For many control is manifested in other ways—by comments about their partner’s behaviour or intentions, by accusations or silence, by what is avoided and made taboo, off-limits, in the relationship. All relationships have rules implicitly or explicitly worked out by partners but unhealthy jealousy will tend to restrict the freedom of partners beyond reason: he or she shouldn’t talk to other men or women when we’re out; we can’t have friendships with members of the opposite sex; he or she should tell me everything they’re thinking or have talked about with colleagues of the opposite sex; he or she should not feel attracted to others and must (or mustn’t) tell me if they are. Couples may share similar thresholds of tolerance but the more limited they are the more it is likely it is we’re seeing something unhealthy.

How it Functions

Jealousy is an emotional response to a triggering event. Events however do not cause jealousy in isolation but only as they are interpreted by the way we understand others and ourselves. These perspectives on reality are not the same thing as reality—we all see the world and ourselves through particular sets of lenses. This is really important to grasp: what we believe about reality seems to be reality but as soon as we allow the possibility that we may be generating a version of things that could be distorted we are at the point of being able to begin some real changes.

We said earlier that jealousy often flows from insecurities developed in childhood and / or through bad experiences. The mind works primarily from deeply rooted emotional models of reality: emotionally-laden beliefs about who were are (models of self) and what others are like (models of others). For efficiency’s sake the emotional mind tends to jump to quick automatic conclusions using ‘rules of thumb’ like ‘this situation X is similar to situation Y I experienced’ or ‘this person X is similar to person Y’. This can be useful for quickly alerting us to dangers but can also cause us to apply inaccurate perceptions to new and different experiences. Becoming aware of this allows us to question our interpretations and be more reflective in our responses. It is not easy to change deep-rooted models of ourselves, others or situations but it is possible to learn.

We need to work on:

- Our beliefs about others

- Our beliefs about ourselves

- Our triggers (events that play into our beliefs)

- Our ability to pause, question interpretations and act differently

How We Can Manage It

A big part of managing jealousy is to be aware of it and wonder about whether it’s healthy or unhealthy: is it based on evidence or based on assumption?

It is very easy to allow those insecurities and past experiences to be automatic default lens through which we judge each situation. Unless, in fact even if, we have clear evidence we should be shouldering the responsibility ourselves before assuming our partner (or a potential rival) is to blame.

This self-questioning pause loosens up our rigid categories imposed on what are often, at  worst, ambiguous events. We can acknowledge that we may be uncomfortable with X or Y situation but we don’t have to turn it into a rigid interpretation with rigid and fixed reactions.

worst, ambiguous events. We can acknowledge that we may be uncomfortable with X or Y situation but we don’t have to turn it into a rigid interpretation with rigid and fixed reactions.

The mind finds it easier to work in simple black/white categories and when we feel stressed and under threat it’s harder to see the greys.

Situations that present challenge often revolve around a demand for exclusive prioritisation and attention from a partner and a demand that others have no interest in them. This is frequently preceded and followed by a felt belief (often unconscious) that we are just not worthy of our partner’s love so that any half-attractive member of (the usually) opposite sex would be able to steal our partner, or their loyalty away from us.

What follows are some strategies you might use. I draw and adapt them from Windy Dryden’s valuable book ‘Overcoming Jealousy’ (Sheldon Press) https://www.amazon.co.uk/Overcoming-Jealousy-Common-Problems/dp/0859699587 . Needless to say, if your jealousy is particularly destructive and leads you to behaviour that is causing you and those around you significant stress (or aggression) you should seek professional help; this link http://www.counselling-directory.org.uk/ may be of help if you’re based in the UK, other countries will have their own directories.

Interventions

1. Identify your Triggers and write a list down of different kind of scenarios in which you experience unhealthy jealousy the most

2. Identify the emotionally rigid beliefs that underlie your jealous responses e.g.:

•My partner must only be interested in me

•My partner should always prioritize me

•No-one else should be interested in my partner

•It would be awful if he/she weren’t only interested in me (or any of the 3 above)

•I could not bear it if any of the above situations were not the case

•If any of the above were not the case it would mean I am not good-enough as a person

3. Understand the internal consequences: that each of these beliefs generate jealousy and lead you to further thoughts and feelings that undermine your faith in your partner and yourself.

4. Note the behavioural consequences:

· Intrusive monitoring

· Blaming and criticizing

· Angry outbursts

· Punitive silences

· Controlling partner’s clothing choices, social outlets

· Limiting your own freedom through fear of what ‘green lights’ it will suggest your partner could have

· Avoiding socializing

· Punishing / potential rivals

5. Learn to dispute your emotionally rigid beliefs and rehearse this arguing with your own mind substituting rigid demands for preferences e.g.:

•I prefer that my partner only be interested in me but most humans aren’t going to be this way and that’s just normal.

•I’d prefer that my partner always prioritize me but this isn’t realistic

• I’d prefer that no-one else should be interested in my partner but it’s unrealistic to expect this and doesn’t mean I’ll lose him / her

•It would be uncomfortable if he/she weren’t only interested in me (or any of the 3 above) but it wouldn’t spell disaster

•I may find it difficult but I could bear it if any of the above situations were not the case

•If any of the above were not the case it would have no bearing on my value as a person. I’d have the same value before, during or after any relationship.

6. Dwell on the overall actual evidence (not assumptions or perceptions) for your partner’s behaviour over the last 6 months: is (s)he giving you clear evidence of infidelity or is his / her overall pattern one of caring and being reliable?

7. Consider using meditation and visualisation to train your mind in how to cope and think differently in your trigger situations (see 1 above). Pick a manageable but tricky situation and play it over in your mind: who’s there? What’s happening? What are you thinking? How are you feeling / responding? What do you think your partner’s attitude is? Now replay this event with the kind of beliefs we just discussed in point 5 and picture yourself relaxing and doing something different (e.g. being friendly to your partner / others present etc.

8. Involve your partner—explain that you want to make life better for both of you but you’d appreciate their help. Explain some of the ways (without demanding) they can support you and how you can negotiate difficult areas together. When your partner understands that your struggles are not malicious but stem from insecurities they are far more likely to be supportive but you must meet them half-way and be willing to make changes.

9. Consider getting some counselling—it may be useful getting qualified counsellor’s support in enabling you to understand yourself better and how you might engage with your difficulties.

IF YOU FOUND THIS INFORMATIVE OR USEFUL PLEASE CLICK TO FOLLOW THE BLOG. THANK YOU!

Acknowledgements and Links:

Dryden W., ‘Overcoming Jealousy’ (Sheldon Press) https://www.amazon.co.uk/Overcoming-Jealousy-Common-Problems/dp/0859699587

Genetic / Cultural Influences:

http://www.nytimes.com/2002/10/08/health/jealous-maybe-it-s-genetic-maybe-not.html

Neuroscience:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21169919

Attachment Theory:

Mario Mikulincer and Phillip R. Shaver ‘Attachment in Adulthood (Second Edition): Structure, Dynamics, and Change ‘

Understanding Our Feelings

Understanding Our Feelings

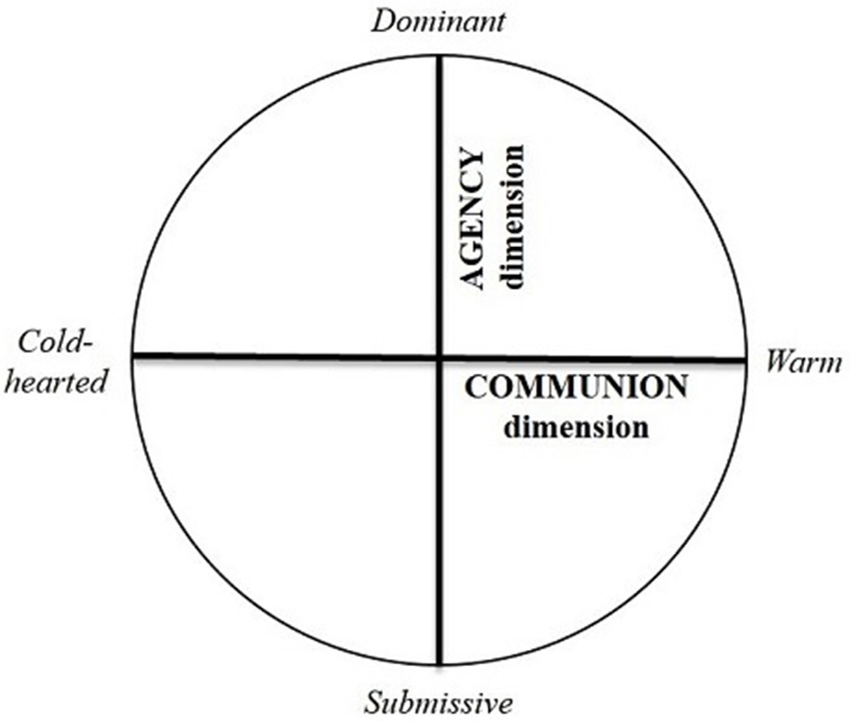

Most of our dealings with others are like games–sometimes they are collaborative games, sometimes they are competitive games, sometimes they are both. Games have rules and in any dealing with others there will be a set of rules (albeit unspoken) or, more accurately, there’ll be at least two sets of rules (yours and theirs) and if you can agree the rules you’ll both play by then maybe there’s a helpful game to be played. What are the rules when you have a fight with your partner? Do you have shared rules? Is there some idea in your fight that maybe something could be won without it being entirely at the other person’s expense?

Most of our dealings with others are like games–sometimes they are collaborative games, sometimes they are competitive games, sometimes they are both. Games have rules and in any dealing with others there will be a set of rules (albeit unspoken) or, more accurately, there’ll be at least two sets of rules (yours and theirs) and if you can agree the rules you’ll both play by then maybe there’s a helpful game to be played. What are the rules when you have a fight with your partner? Do you have shared rules? Is there some idea in your fight that maybe something could be won without it being entirely at the other person’s expense?

Jealousy is a common and powerful emotion, one that draws in a number of other powerful ‘negative’ emotions such as anger, anxiety, fear and hurt. It is one of the top causes of homicide by spouses internationally and is experienced more by men (60% v 40%) than women. Even when this is not the case it can cause serious disturbance to relationships and to the people involved, creating severe limitations to the freedom of both the sufferer and their partner.

Jealousy is a common and powerful emotion, one that draws in a number of other powerful ‘negative’ emotions such as anger, anxiety, fear and hurt. It is one of the top causes of homicide by spouses internationally and is experienced more by men (60% v 40%) than women. Even when this is not the case it can cause serious disturbance to relationships and to the people involved, creating severe limitations to the freedom of both the sufferer and their partner. The main personal reasons we experience jealousy is because of past experiences: we have been burned in previous relationships or we have experienced displacing rivalry in childhood—or both. The Oedipal dynamics whereby we experienced the loss of maternal or paternal attention—or perceived this–due to the other parent or a sibling taking some of it away. We needn’t buy into a full acceptance of a Freudian view that at an early stage boys desire to sleep with their mothers and feel threatened that their fathers wish to castrate them to see that children—girls no less than boys—experience losses when a third party vies for attention. How we respond as adults to the potential vying of attention when a third party arrives on the scene is often deeply influenced by these formative years although some of it will have been learnt in the stages prior to our ability to remember or verbalise.

The main personal reasons we experience jealousy is because of past experiences: we have been burned in previous relationships or we have experienced displacing rivalry in childhood—or both. The Oedipal dynamics whereby we experienced the loss of maternal or paternal attention—or perceived this–due to the other parent or a sibling taking some of it away. We needn’t buy into a full acceptance of a Freudian view that at an early stage boys desire to sleep with their mothers and feel threatened that their fathers wish to castrate them to see that children—girls no less than boys—experience losses when a third party vies for attention. How we respond as adults to the potential vying of attention when a third party arrives on the scene is often deeply influenced by these formative years although some of it will have been learnt in the stages prior to our ability to remember or verbalise.

worst, ambiguous events. We can acknowledge that we may be uncomfortable with X or Y situation but we don’t have to turn it into a rigid interpretation with rigid and fixed reactions.

worst, ambiguous events. We can acknowledge that we may be uncomfortable with X or Y situation but we don’t have to turn it into a rigid interpretation with rigid and fixed reactions.